How to build a private 5G network and IoT platform for an enterprise Edge

The combination of the three (independent) technology areas edge computing, private/dedicated 5G networks and IoT could be the hottest cake you find in the telco/IoT industries right now. These three concepts are not simple for everyone to digest. If you’ve worked with 5G for the past ten years you probably haven’t spent too much time learning about cloud computing, microservices, containers and enterprise IT architectures. If you are an IT network consultant, the node named “UPF” in a 5G core probably sounds like a packet delivery supply chain company. A lot of people also believe that private 4G/5G networks are not suitable, useful or cost-effective for enterprises to install and use.

In this article, I will explain what these three tech areas are made of and how they overlap. I also describe my own lab setup which you could copy and get your own, private 4G (soon 5G) mobile network and IoT platform running on an edge cluster.

Let’s start off by taking a look at the three technology areas and describe what they do and why they are important.

Internet of Things (IoT)

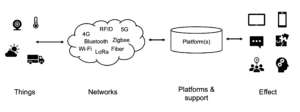

There is no one definition of what IoT actually is. In the book Things you should know about the Internet of Things, I stick to the “definition” shown in the figure below which holds for pretty much any IoT solution. It describes that IoT consists of the following four layers:

- A Thing is a device that has a network interface and can uniquely identified within a network.

- Networks can be of any kind. The standards shown in the figure below are just examples. This article focuses on private/dedicated 4G/5G networks, which provide quite unique features related to Quality of Service and mobility. We get back to this further down.

- The Platform layer is responsible for managing Things, receiving and converting data, storing data in various ways, creating rule chains to trigger events and alarms, visualise data and provide Application Programming Interface (API) to other systems. If you’re interested in learning more about IoT platforms, this is an intro article. There’s a lot more information in the book I referred to above.

- What we ultimately want to achieve with an IoT solution is to create an Effect. This could range from visualising water levels to feeding a machine learning algorithm. The desired effect has to be measurable and fully understood before an IoT solution is designed.

A term that often pops up when working with industrial IoT is Industry 4.0. The reason is that a lot of robots, cobots, machine learning models, condition-based monitoring, digital twins, asset/people tracking and other stuff that Industry 4.0 is about need a lot of data from many devices and sensors to function properly. Reliable IoT is a requirement for all these technology areas to take off in industries, production environments, hospitals, smart cities and enterprises in the years to come.

Private/dedicated 4G/5G networks

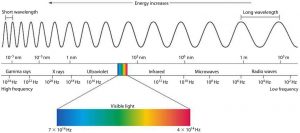

As mentioned above, machine learning algorithms and many other consumers of data demand not only IoT data, but good IoT data showing up at the right time without any packet loss. This requires sensors of decent quality, but also wireless networks that can deliver deterministic coverage, mobility, security and quality of service in a way not offered by technologies in unlicensed 2.4 GHz or 5-6 GHz frequency bands.

A very clear trend in many business verticals is therefore to consider deploying an own, local mobile (4G or 5G) network to connect CCTV cameras, trucks, forklifts, digital signage screens, drones at construction sites, combined indoor/outdoor asset tracking systems, Augmented Reality glasses and other services and gadgets.

From an architectural perspective, Wi-Fi is different from a mobile network as it doesn’t come with a core network, and for many years there has been zero chance for an enterprise to install, configure and manage their own 4G/5G infrastructure. If you talk to an IT organisation, they even refer to Wi-Fi as “wireless” as it has always been the only relevant choice when unwiring a Local Area Network. 4G and 5G have been seen as primarily outdoor mobile network services provided by Mobile Network Operators (MNOs).

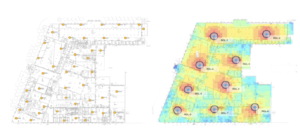

Within just a couple of years, this has changed completely. A private 4G or 5G network can now be deployed by an enterprise with the same ease as a Wi-Fi system. The price point has gone down and is on par with and sometimes lower than Wi-Fi. One major reason is that the coverage you get from a 4G/5G small cell is 5-10 better than what a Wi-Fi AP offers. The figure below shows a Wi-Fi design next to a 4G small cell design in the same building. Note that the output power per radio node in the 4G network is typically lower than the output power configured for the Wi-Fi APs. The improved 4G/5G coverage comes from better chipsets and how the radio protocol is standardised. The reduced node count can be translated into a lot less hardware, SW licenses, cabling and PoE switch ports needed.

The new 4G/5G networks are simple to manage even for an organisation not familiar with how to plan, design or operate a mobile network. Integration to existing IT services and reuse of existing functions like DHCP, client certificates and segmentation of traffic looks just like the IT technicians are used to. Even the management systems have the same look and feel and provide toolboxes for API integration towards existing management/ERP systems.

The quick adaptation of 4G/5G to enterprises has been enabled by some important factors. IoT is of course one. Here are three others:

1. Access to spectrum/frequencies for non-MNOs to run private 4G/5G networks on. The figure below shows some of the most common Radio Frequency spectrum bands which either are licensed (often to MNOs), unlicensed (for everyone to use) or lightly licensed (free or very cheap to use for anyone). The Citizens Broadband Spectrum Service (CBRS) in the US is one such lightly licensed spectrum model. Similar models exist in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK with many more European countries to follow in the coming years. This said, many MNOs are also using their own spectrum to build private networks.

2. Open source communities and movements. What will fuel the private 5G market even further is the fact that open source software exists for pretty much anything today. Regardless if you want to develop an IoT platform or a 5G core network, you can find and grab already existing software components or entire projects from Github and get started. With a cloud-native approach, services can be disaggregated and end up as loosely connected microservices and often scale from a Raspberry Pi up to entire datacenters. Open RAN (O-RAN) is another type of (related) movement which aims to break the traditional vendor silos in cellular networks and disaggregate layers in order to open up for different vendors to be used in the same solution.

3. Cloud-native computing. 4G core networks (explained below) used to be extremely complex, costly and bulky. An MNO typically has one per country and in some cases one serving the radio networks in several countries. Nowadays it is possible to build these core networks on virtual machines or even on microservice architectures in container environments. This allows for an entire network to be scaled down and run on a single off the shelf server. Services are interconnected via API. If we need more resources of some type (signaling, mobility, user plane etc.), new containers of the right type can be started in milliseconds and connect with existing services via API.

The cloud-native evolution is further explained in the figure below where we’re looking at an enterprise network with three different wireless networks. The first one is a traditional Wi-Fi AP being connected to a WLAN Controller (or just to a switch). Authentication options are left out in this example.

The second network is a 4G one. Compared to Wi-Fi, we need to add an Evolved Packet Core (EPC) network which roughly consists of:

- A control plane responsible for authentication, authorization, policy control/enforcement and seamless mobility.

- A user plane taking care of the IP packets being transmitted. This is more or less routing of packets going to/from the mobile devices. A Netflix session, the content of a website, emails etc.

The third network introduces the 5G core which contains pretty much the same functionality as the 4G core, but everything is renamed as “Functions” (think: microservices). “AMF” is for example the Access and Mobility Function. So the blue marked boxes in the 4G core and the blue boxes in the 5G core are covering the same functionality. The same goes for the orange boxes. The ones with green text represent new 5G core features adding structured/unstructured database storage, network exposure (API), service discovery and message bus and something called Networks Slicing. All of those (except the slicing) are features you find in cloud-native computing and container environments. The question is: Who benefits the most from 5G being extremely flexible and scalable to deploy? Well, private/dedicated 5G networks is a good bet, especially when running it at edge locations.

All of these transition factors play important roles in the rapidly approaching future where private 5G networks will be deployed in scale for industries, hospitals, enterprises and universities and sit next to existing Wi-Fi networks. Do we need both? Definitely:

- The bandwidth demand is there and will only grow with more video and AR applications.

- Voice and video services of different types (native dialling, Teams, Whatsapp, Facetime, Webe, Hangouts, VR calls or other personal favorites app) will become more important in the post-pandemic world.

- There are many use cases Wi-Fi simply isn’t suitable for that 5G will handle with ease. Think of anything that has to perform in a congested area, something that moves, something that has to deliver data deterministically, something located in areas where you can’t mount radio nodes every 30-50 meter or something requiring a high level of security.

- Mobile network indoor coverage is poor in many countries. A private/dedicated network could be used to facilitate Neutral Host Networks (NHN) and allow for new types of RAN sharing models. The UK is forerunners in this area with the Joint Operators Technical Specifications (JOTS) which allows for 3rd party players and NHN providers to build indoor networks that the MNOs can utilize via agreements.

The Edge environment

A simple way of explaining where we find the Edge would be to say it sits between the cloud and end devices or services. The purpose is generally to distribute compute, storage and database functions closer to the device to cut costs, lower latency or provide local survivability of services.

One example could be a climate system and a surveillance camera (the “devices”) mounted in a bus. Let’s say they are connected to a public cloud service (the “cloud”) via a mobile network. An Edge node could in this case be a vehicle-mounted server responsible for collecting, analysing and acting on local data before it’s sent to the cloud.

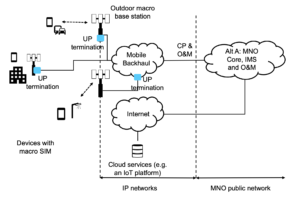

Where and what the Edge is really depends on who you are and what you offer. If you’re a Mobile Operator, you might see your Edge as the edge of your mobile network which consists of radio base stations (the “devices”) and a mobile core network (the “cloud”). This is illustrated with the “UP termination” boxes in the figure below. The purpose of distributing the UP in this case is often to cut latency for specific applications. The “device” could also be any terminal provisioned with a SIM card or eSIM.

If you’re an enterprise, an energy company, a system integrator or a production company, your Edge is often a local data center or something even closer to your end devices (see examples in the figure below). The cloud is normally a private or public cloud reached via a WAN or SD-WAN connection.

For these types of organisations, “low latency” could be a reason to install a local 5G network, but these factors are more common drivers:

- Local survivability. If someone cuts the WAN to the site or if there’s a power outage in the area, the locally deployed mobile network will still deliver.

- Simpler segmentation. If the traffic leaves the site and comes back again via the company firewall, segmentation could become a hassle. Especially if the number of devices grows and you run out of IP addresses in a defined scope. If the local 5G network terminates the traffic on premise on an Edge node, things will look just like in a Wi-Fi network, and you can use private address ranges with a large scope.

- High security and trust. Most enterprises want their traffic and certificate handling to stay inside the enterprise network.

- Cost control.

- No dependencies and high flexibility. Owning and managing your own network means you can also scale it when you need. If there is more traffic or more users, you can handle the situation by adding more radio nodes.

- Run the 5G networks on non-macro spectrum (either lightly licensed or a licensed chunk which is not used by the macro network in the area). Doing so means you don’t have to plan out your radio network with respect to the macro network energy. This leads to a much more lean and simple design, and the range per radio node is greater without competing noise and interference.

Building your own enterprise edge + 5G + IoT solution

Alright, now when we know what private 5G, IoT and edge computing are about and how they are used together, let’s get our hands dirty and combine these technology areas in practice. Building an own lab and testing things is often the best way to learn how stuff actually work. The setup I will demo looks like in the figure below and is based on the following components:

- Intel NUC with 64GB RAM, a Xeon processor with 8 cores and 3x1TB of SSD storage. Although this is a single node, it will from a Hyperconverged Infrastructure perspective be seen as a single node “cluster”.

- Nutanix Community Edition which provides a hypervisor (AHV), operating system (AOS), virtualization of the infrastructure (storage, processor, network interfaces), Kubernetes and a management plane for FCAPS (Fault/Configuration/Alarm/Perfomance/Security/Software management).

- On the Nutanix cluster, we spin up two Virtual Machines running:

- A 4G mobile core network from Celona (yes, I said I will build a “5G network” to catch eyeballs, but from a demo point of view 4G and 5G are indistinguishable, and I can easily upgrade the setup to 5G Stand Alone once the SW and NR radios are around later this year). This core network is created and adapted for IT organisations and all configuration that has to be done is related to IP addresses, DHCP relay, VLANs, Quality of Service etc. Just like in a Wi-Fi network. Installation of the image file on the VM is a quick and very straightforward process.

- Nutanix Karbon Platform Services (Kubernetes cluster) where we will run the IoT platform and related services.

- 4G base station (also referred to as an Access Point) from Celona.

- Laptop where we simulate various sensors with Python scripts. “Hey, why don’t you use a 4G sensor for this?”. Well, I don’t have one with 4G connectivity at home, so I do it like this instead.

- A Huawei router used to connect the laptop to the Celona 4G network.

I leave the IP configuration out here and move directly to the setup. The following steps were carried out when setting up this environment:

1. Install Nutanix CE on the NUC to bring up the edge cluster. Several guides on how to do this are available. Here is one: https://getninjad.com/2018/12/29/nutanix-home-lab

2. Once the Nutanix platform is up and running, set up the VM for KPS. This will provide:

- A Kubernetes cluster where you can run containers (one of them will be your Thingsboard open source visualization platform, see below).

- A service domain where you can configure ingress of data from the IoT device, a queue for incoming packets, conversion of the data to desired formats and the API calls for pushing the data to the IoT platform.

Luckily, my friend Emil Nilsson at Nutanix has written an excellent guide on how to do all of this. If you run it through you’ll set up an MQTT broker, ingest control for data packets, a Kafka queue, a consumer group fetching packets from this queue and the IoT platform (Thingsboard) which is populated with data via their API. You find the guide here: https://github.com/voxic/Thingsboard_on_KPS

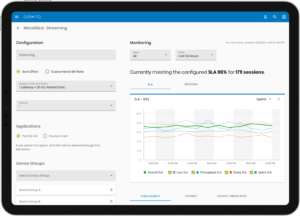

3. Setting up your 4G network is a very straightforward process where you start off installing your Celona core network on a VM in your Nutanix cluster and then log in to the Celona Service Orchestrator where all configuration of IP addresses, DHCP, sites and SIM provisioning is done (see figure below for example view). Important here is that you don’t need to know anything about the underlying 5G core network services described above. It’s all delivered as a service and the installation is done in no time.

4. If you need a Python script to emulate the sensor on the laptop, Emil is your friend again. Here’s a link to one of his other Github projects with sample code you could use as the base: https://github.com/voxic/weatherstation-simulation

The management tool for both the Nutanix environment and the Celona network are developed for IT organisations with an API-first mindset and if you have configured Wi-Fi networks before you will recognise almost everything on the radio/IP side. The main differences in configuration are related to ability to define quality of service per application/device and actually trust that your radio network delivers under load.

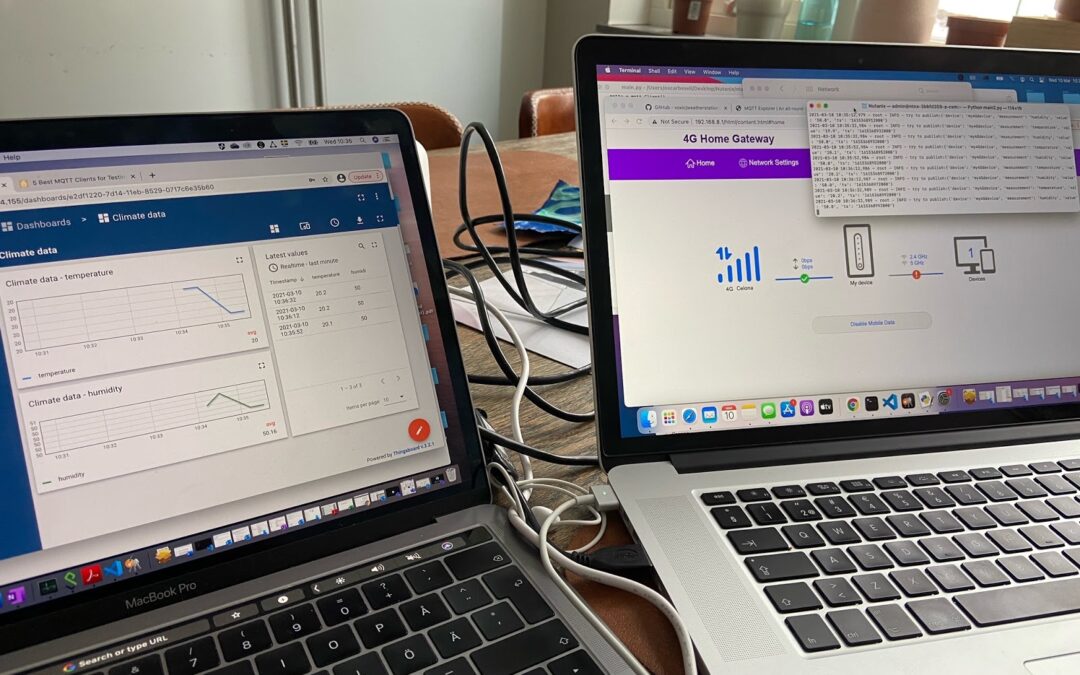

The result of this setup is an IoT device communicating over a private enterprise 4G network, feeding the open source IoT platform with sensor data which is displayed in widgets. The result of the test setup is shown in the figure below where we see the Thingsboard dashboard to the left and the script emulating the sensors on the screen to the right.

What’s next?

Now when our test environment is up and running, we could relax and just watch our sensor data flow through the 4G network via our edge cluster to the IoT platform dashboard. When we have done that for ten seconds, we can move on using our cluster and add the next wave of projects. This is what I’m aiming for:

- Get more devices supporting the configured 4G band. I’m looking at a couple of video cameras. The ultimate goal is to test a Celona feature called Microslicing which allows you to configure individual quality of service classes per application/device. You find a really good demo on how this is setup in order to give different priority for different services over here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UD7sS7P3wGo

- Add an Artificial Intelligence application to your Kubernetes cluster. In my case, I will feed an image recognition application with one of the camera streams. The application identifies if someone or something is moving outside my home during nighttime, and if the object is a human I will save the video and send an event to my home automation system which is based on https://www.home-assistant.io (this also runs on KPS in my Nutanix cluster).

- Add more applications to the cluster. Apart from the AI application and the Home-Assistant automation platform, I’m also planning to add an open source LoRa Network Server (Chirpstack), a location engine for asset tracking and a virtual WLAN controller (Ubiquiti). This will result in the configuration shown in the figure below.

- Send your IoT data to public cloud services. Nutanix provides cloud connectors to AWS, Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud. The setup is easily done by setting up a new consumer group in the KPS data pipeline and forward incoming packets to one of the Hyperscaler clouds as well.

- Upgrade the 4G network to 5G. This will happen during the summer/autumn 2021.

In the end, what your managed edge cluster will look like is really a question of use cases and desired application support. Build – play – have fun!

I hope you enjoyed this article. Please feel free to reach out if you have any questions regarding the setup or any of the technology areas discussed.